On 30th October 2024, in her first Budget Chancellor Rachel Reeves has the very challenging task in setting out the government’s fiscal plans to increase investment spending, raise economic growth and fix the budgetary “black hole” whilst retaining fiscal credibility and not reneging on election pledges. The arithmetic will be tight. Tax rises, freezing of tax thresholds and real-term cuts for many government departments seem inevitable, as does an increase in government borrowing.

There will be scrutiny on the borrowing to be funded through the issuance of ‘gilts’ (i.e. UK government bonds). Investors’ reaction to the scale of this requirement and their willingness to absorb this additional issuance will determine whether it pushes the cost of government borrowing up or down.

Although a dry subject, Arlingclose is occasionally asked about gilts in general and why they are referred to as such. So let’s start with a step back in time.

What are gilts?

Gilts are debt securities issued by the UK government, representing a liability denominated in sterling. They were first issued in 1694 by the newly established Bank of England to help finance the government's war effort against France (the Nine Years War 1689-1697). Their issuance marked the beginning of the UK's government bond market, which has since become a cornerstone of government financing.

In 1998, the UK Debt Management Office took over from the Bank of England for managing the issuance and oversight of gilts on behalf of HM Treasury.

The term "gilt-edged" refers to the original gold leaf trim on the government bond certificates but, more than that, it symbolises the high security and reliability of these bonds. The government's consistent record of meeting interest and principal repayments provides investors with a secure investment option backed by the creditworthiness of the UK government.

Today, gilts remain a fundamental feature of the UK’s debt management operations. These include conventional and index-linked gilts with an array of maturities, offering a stable source of financing for the government while providing investors with secure and liquid assets catering to different risk appetites and investment strategies.

The regular issuance of gilts also helps to shape the broader interest rate environment, influencing rates across the economy.

Types of gilts

Conventional gilts form the majority of the market (approximately 76%) and offer a fixed cash payment, referred to as ‘coupon’. For example, a gilt with a 3¾% coupon maturing in 2052 signifies that investors will receive 3.75% interest per annum divided into two equal semi-annual payments, until the principal is repaid in 2052.

Index-linked gilts, first introduced by the UK in 1981, adjust both the semi-annual coupon payments and principal in line with inflation, as measured by the UK Retail Prices Index (RPI), with a lag. This feature protects investors from inflationary erosion of their returns, offering a hedge against rising price levels. Given their inflation linkage, index-linked gilts tend to behave differently from conventional gilts, especially in periods of economic volatility.

How much gilt issuance is outstanding and when does it mature?

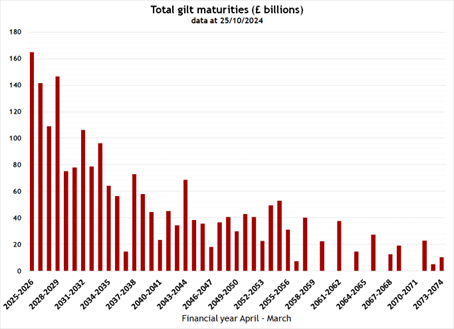

As of 25th October 2024, the total nominal amount of gilts outstanding, including inflation adjustments for index-linked gilts, stood at just over £2.5 trillion, comprising £1.95 trillion in conventional gilts and £615 billion in index-linked gilts. There was a big increase following the financial crisis in 2008/09 and again during and following the pandemic.

The Bank of England holds approximately £558 billion in gilts, about 22% of the total gilt market, as part of the Bank's Asset Purchase Facility used for quantitative easing.

Non-UK investors hold about 29% of the outstanding gilts, reflecting the broader role of gilts in international investment portfolios.

Maturities net of government holdings. The profile will change as new gilts and further tranches of existing gilts are issued.

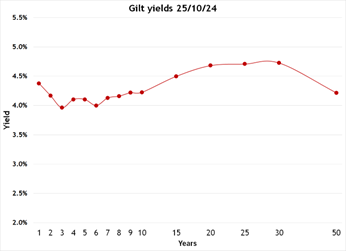

Market Pricing and Yields

The price of a conventional gilt is typically quoted per £100 nominal face value and can be above or below £100. The face value is the amount the investor will receive at maturity.

Gilts are actively traded in capital markets and their prices fluctuate with changing economic conditions and outlook, particularly with respect to interest rate and inflation expectations. Prices also hinge on investors’ perception of fiscal credibility - the government’s current and future debt burden, its cost and the discipline to stay within medium and long-term borrowing plans. Prices will also reflect demand from investors for existing gilts and new gilt supply.

The yield is different from the coupon. The redemption yield, also known as the yield-to-maturity, gives an indication of the actual return on capital that the investor will receive taking into account the price at which the gilt is bought and holding it to maturity.

For index-linked gilts, the inflation protection feature adds complexity to their pricing dynamics, making them behave differently compared to conventional gilts during periods of changing inflation expectations.

Redemption yields and the inverse relationship of gilt prices and yields

As with bonds, gilt prices and yields have an inverse relationship; as the price of a gilt rises, its yield falls, and vice versa. Remembering that on maturity, the capital repaid is the nominal amount of the gilt, not the price at which it was bought, as the gilt price rises the investor is effectively paying a premium for a series of fixed cash flows and so the yield, i.e. return, falls.

The UK Debt Management Office (DMO) website offers extensive data on the issuance, maturities and yields of gilts.

For those unfamiliar with bond markets and terminology, phrases such as “bonds/gilts rallied” can cause some confusion. A rally in the gilt market means that gilt prices have risen, consequently meaning that gilt yields have fallen. As a result, we often must remind ourselves to be precise when describing gilt movements.

Why do gilt yields matter for UK public sector authorities?

The shape of the yield curve (more in Joe Scott-Soane’s Insight), the level of gilt yields for maturities from 1 through to 50 years and their future path, has significance for UK local authorities. It is the reference point to which a margin is added to derive the rates at which local authorities borrow when sourcing loans from the PWLB Lending Facility (or Department of Finance for authorities in Northern Ireland).

Market uncertainty contributes to volatility in gilt and other sovereign bond yields. This is often centered around monetary policy moves or uncertainty over the outcome of economic or political events, such as the UK Budget on 30th October, and the potential impacts on growth and inflation. Political uncertainty is currently high, as Finn Watson describes in his recent Insight article on the Trump-vs-Harris implications for gilts.

These factors are integral to Arlingclose’s interest rate forecast, which informs our advice to clients on treasury management decisions, in particular the domestic and global economic and political drivers which could likely move gilt yields, and consequently PWLB rates, up or down over the short- to medium- term.

If you would like more information on our economic and interest rate forecasting services or our debt advisory services, please email treasury@arlingclose.com.

Related Insights

Local Authority Borrowing Option – National Wealth Fund