The US labour market has continuously surprised with its strength. It’s not the only developed economy labour market that has, but it’s fair to say that it’s had a much larger effect on global bond markets and interest rate expectations than others. The last set of labour market data suggested a return to normality, but begs the question about whether the US labour market just experienced a month of soft growth or whether this is the start of a developing weaker trend.

The headline labour market numbers look good; the average monthly increase in non-farm payrolls over the past 12 months was 234k and the unemployment rate was 3.9%. Both figures are healthy, and while April’s data represented a somewhat weaker picture than recent months (payrolls +175k, unemployment rate +0.1ppts), there were three months in the past year where the payroll gain dropped below 200k and subsequently saw a pickup back to higher numbers.

However, there were a few underlying figures that suggest the labour market may be loosening faster than the headline numbers suggest.

The number of respondents identifying as part time for economic reasons has risen around 600k over the past year, split broadly evenly between being part-time due to slack business conditions and only being able to find part time work.

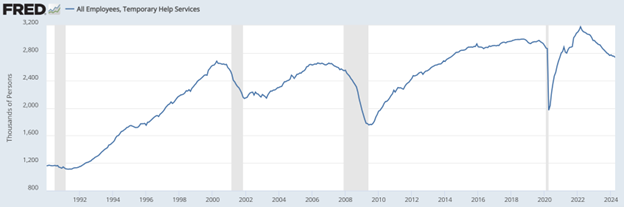

The number employed in temporary help services, arranging temporary employment for others, has been falling since 2022, down 444k over the past two years. Traditionally, a decline in temporary help services presages a recession, but we have to treat the current downturn more cautiously due to a possible unwind from the pandemic-related labour market issues, particularly because overall staff levels continue to rise (albeit the household survey suggests employment has recently plateaued). However, the level is now below pre-pandemic levels, and taken together with the rise in part-time work, it could suggest a deteriorating situation.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees, Temporary Help Services [TEMPHELPS], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TEMPHELPS, May 17, 2024.

*Shaded areas in charts indicate US recessions

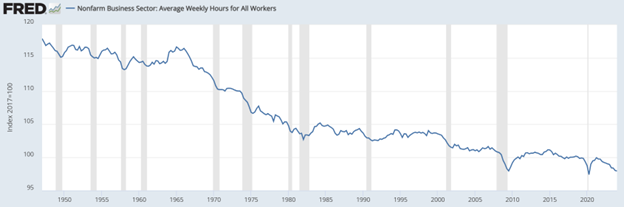

Another labour market indicator that usually occurs before and during a recession is a decline in average weekly hours. The average weekly hours index (2017 = 100) for all workers has fallen from a post-pandemic peak of 99.96 in Q1 2021 to 97.95 in Q1 2024. This may point to labour hoarding, with firms holding onto staff due to the difficulties finding expertise following the pandemic.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Nonfarm Business Sector: Average Weekly Hours for All Workers [PRS85006023], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PRS85006023, May 21, 2024.

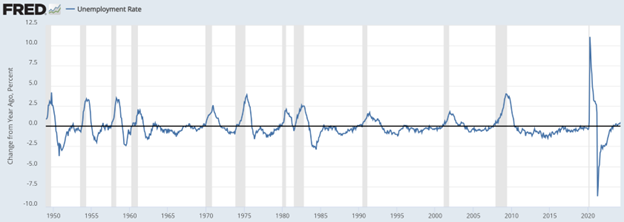

Lastly, an increase in the unemployment rate compared to the prior year does not always communicate a recession, but is a pretty strong indicator. In April 2024, the 3.9% rate was 0.5 percentage points higher than the year prior rate. The unemployment rate is still very low historically, but it’s a fairly large change absent of a recession.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE, May 17, 2024.

Clearly post-pandemic factors are affecting the normal functioning of the labour market and the signals that various labour market data are sending. Businesses appear to be holding onto and employing new permanent staff, suggested by continuing unemployment insurance claims for unemployment running at relatively low levels (although, again, higher than pre-pandemic levels and recently rising). If labour hoarding is happening in reality, there must be rate of activity growth or slack in the labour market at which businesses decide that hoarding is no longer necessary.

This may already be happening; consumer sentiment around the jobs market has recently deteriorated, Q1 US GDP growth was weak relative to prior quarters and the ISM employment sub-indices have been around or below 50, suggesting that the labour market loosening may have further to run.

As we have seen, when these trends start to impact on headline labour market figures, interest rate expectations and bond yields move significantly. With the US financial markets continuing to have an outsize impact on the UK, a sharper correction in US labour market data could place downward pressure on gilt yields.

Related Insights

Bank of England to Overhaul Its Forecasting Approach

Is the path of UK inflation more like the US or Eurozone?

Common Pitfalls in Your Year End Accounts (and How to Avoid Them)