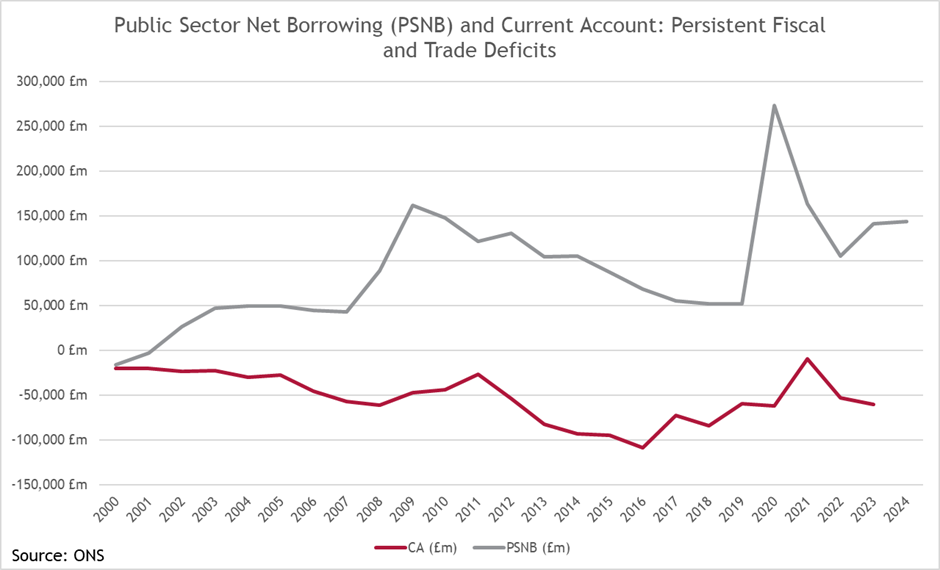

Two defining features of Britain’s macroeconomy have been its persistent fiscal and current account deficits. From the end of WWII to today (1945-6 to 2023-4), the UK had fiscal deficits in 68 of the past 79 years, with the last surplus occurring briefly under Blair in the 2001-02 year. Similarly, the UK has seen consistent trade (current account) deficits every year since 1998. While such persistent and structural deficits are not a problem by themselves, the Treasury faces several headwinds in meeting its fiscal targets such as low growth, stagnant productivity, lacklustre tax receipts, and high real interest rates. Additionally, Britain’s trade deficit poses further challenges, acting as a drag on GDP, exacerbating the fiscal deficit, and increasing the economy’s exposure to external shocks in an increasingly volatile global environment. It also reflects the long-term erosion of the country’s industrial and manufacturing base.

A key to determining whether the UK’s fiscal position is sustainable is its interest rate growth differential, that is, the difference between the real interest rate (R) and the real growth rate of the economy (G). If the economy is growing faster than the interest burden on debt (G > R), the government can stabilise or reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio without requiring a budget surplus because the economy’s expansion outpaces the accumulation of interest obligations in real terms. This means that even with a primary deficit, the relative size of the debt stock declines in time as GDP grows, reducing the fiscal strain. Conversely, if R > G, the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise unless the government runs fiscal surpluses, as interest costs compound faster than the economy’s ability to generate real output and revenue.

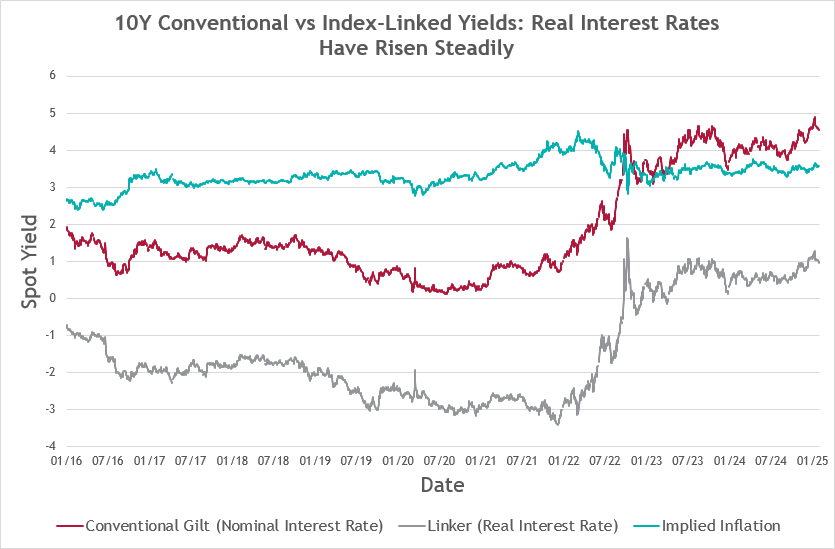

The real interest rate faced by the government can be approximated using the yield on inflation-linked gilts. Unlike conventional gilts, which contain an inflation risk premium in their yields, inflation-linked gilts (linkers) provide a fixed real yield plus an inflation adjustment based on RPI. This distinction allows us to extract inflation expectations from the spread between nominal and linkers. As shown in the graph below, the elevated yields on 10-year gilts in recent years has been primarily driven by rising real interest rates rather than shifts in medium-term inflation expectations.

The current high real interest rate environment presents significant fiscal challenges, as it accelerates the accumulation of interest expenses and adds further pressure to the deficit. Within the interest rate growth differential framework, economic growth and corresponding tax revenues must increase to prevent the debt burden from expanding. However, growth has failed to keep pace with rising interest rates, making fiscal consolidation necessary to maintain the UK’s fiscal position. With growth lagging behind interest rates, stabilising the debt-to-GDP ratio will require either an acceleration in productivity-driven expansion or sustained fiscal restraint. In this environment, maintaining credibility with investors – who finance both the budget and current account deficits – becomes increasingly vital, as deteriorating confidence could further elevate borrowing costs and exacerbate external vulnerabilities.

Recognising these pressures, Chancellor Rachel Reeves has committed to a fiscal consolidation strategy centred on balancing the current budget and reducing net debt as a share of GDP. However, with higher debt-servicing costs absorbing fiscal space and economic growth remaining subdued, the feasibility of achieving these targets without further tax increases or spending cuts is unlikely.

In her October Budget, Reeves introduced a set of self-imposed fiscal rules aimed at ensuring fiscal consolidation and stability, including a commitment to balancing the budget for day-to-day spending (excluding investment) and reducing net financial debt relative to GDP by 2029-30. As part of this strategy, she set aside a £9.9 bn buffer, or ‘fiscal headroom,’ to absorb unforeseen economic changes. However the Treasury recently recorded a £15.4 bn budget surplus in January - £5 bn below the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) forecast of £20.5 bn – effectively eliminating this headroom unless corrective measures are taken in the Spring Statement today.

This shortfall leaves Reeves with a set of politically difficult choices. One option is to deviate from her “iron-clad” fiscal rules, allowing for a wider deficit. This would undermine investor confidence, potentially leading to higher gilt yields and consequently a greater interest burden as demand for UK debt weakens. Alternatively, she could raise taxes, though this has been ruled out. The most probable course of action is spending cuts, but given recent commitments to increase defence spending, reductions would likely come at the expense of public services. Departments have already been instructed to model cuts from 3% to 11%. While boosting economic growth would offer a way out of this fiscal bind, achieving meaningful growth in the short term is difficult and any regulatory reforms aimed at stimulating investment and productivity would likely come with significant policy lag, limiting their immediate effectiveness.

Beyond its immediate fiscal impact, consolidation may also contribute to narrowing the current account deficit, as suggested by the twin deficits hypothesis. In macroeconomics, this hypothesis posits a causal link between budget and current account balances, based on the national accounting identity that an increase in the budget deficit must be offset by either a reduction in net exports or investment. If the twin deficits hypothesis holds, the UK’s ongoing fiscal efforts could, in theory, help address both imbalances. However, empirical evidence complicates the discussion. Some studies suggest that past attempts to improve the current account through fiscal consolidation during the Bretton Woods era, were either ineffective or counterproductive in the UK. Others find a strong, albeit imperfect, positive relationship between fiscal consolidation and current account improvements across 17 OECD countries. Given these mixed findings, it is questionable whether fiscal efforts alone can solve the trade issue and that a more structural approach is required.

The persistence of the trade deficit is reinforced by long-term structural factors, including deindustrialisation, post-Brexit trade barriers, and global trade headwinds. While Britain’s services sector remains a major export strength, it has not fully offset the decline in goods exports resulting from deindustrialisation. This has deepened the UK’s reliance on imported goods for both domestic consumption and manufacturing inputs, exacerbating the trade imbalance. Additionally, increased formal and informal trade barriers with the EU, alongside rising American protectionism, likely constrain potential export growth. While a depreciation of sterling, in theory, could improve the trade balance by lowering the relative price of UK exports, both exports and imports tend to be relatively inelastic, meaning depreciation alone is unlikely to bring about a meaningful current account correction. Moreover, sterling’s exchange rate is influenced by a wide range of factors beyond the twin deficits, some of which may push the currency in the opposite direction, limiting its role as a natural stabiliser. It appears that the trade deficit is here to stay.

With fiscal headroom shrinking and structural trade imbalances entrenched, the UK faces difficult choices in navigating its macroeconomic challenges. Fiscal consolidation may help restore stability, but whether and how the government will achieve its plans for budget balance remains to be seen. The broader economic impact of these measures is also uncertain. Without a stronger growth trajectory or meaningful productivity gains, the long-term effectiveness and impact of fiscal consolidation doubtful. In the absence of a comprehensive strategy to address these deeper structural issues, fiscal and external imbalances are likely to remain a defining feature of Britain’s economic landscape.

If you would like more information on our economic forecasting or borrowing cost projections, please contact us at treasury@arlingclose.com or 08448 808 200.

Related Insights