With Trump’s tumultuous presidency in full swing, trade wars, tariffs, and deficits have dominated the news cycle, leaving many countries scrambling to figure out how to adapt to emergent illiberalism in global trade. Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported goods, making them more expensive for domestic consumers and, in theory, encouraging the purchase of locally made alternatives. They are often used as a tool of economic policy to protect domestic industries, reduce trade deficits or exert political pressure on trading partners. Given the significant departure of the US administration away from the post-war system of free trade America created, the impact of Trump’s trade wars will likely be widespread, affecting the path of monetary policy, inflation, growth, and diplomacy on both sides of the Atlantic.

Statements from US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick suggest that the current tariffs may be part of a broader strategy and negotiation process, particularly in efforts to establish a new North American trade agreement to replace the USMCA, which Trump signed in 2018. Determining the scope of future actions and whether tariffs will continue to escalate or if a compromise will be reached is difficult to forecast given the President’s mercurial nature.

Announced 25% tariffs on certain goods from Canada and Mexico have now been suspended twice, but have still caused retaliation from Canada. Tariffs on China have been imposed at 10%, then doubled to 20%. China has also implemented retaliatory tariffs.

The US has also imposed a blanket 25% tariff on all steel and aluminium imports, which prompted further retaliatory tariffs from Canada and new measures from the EU on certain US imports. Beyond these measures, Trump has also vowed to impose separate 25% tariffs on the European Union, asserting that the bloc was “formed in order to screw the United States” and that “they have done a good job of it, but now I am President” (the EU was actually partly formed to reduce conflict on the continent, but was also welcomed by the US as a way of meeting the Soviet threat at the end of the Second World War).

While it hoped to gain exemptions after the largely successful visit from Starmer, the UK has also been hit by the steel and aluminium tariffs. In a joint press conference, Trump spoke favourably of his relationship with Starmer, stating, “I think there’s a very good chance that in the case of these two great, friendly countries, I think we could very well end up with a real trade deal where the tariffs won’t be necessary.”

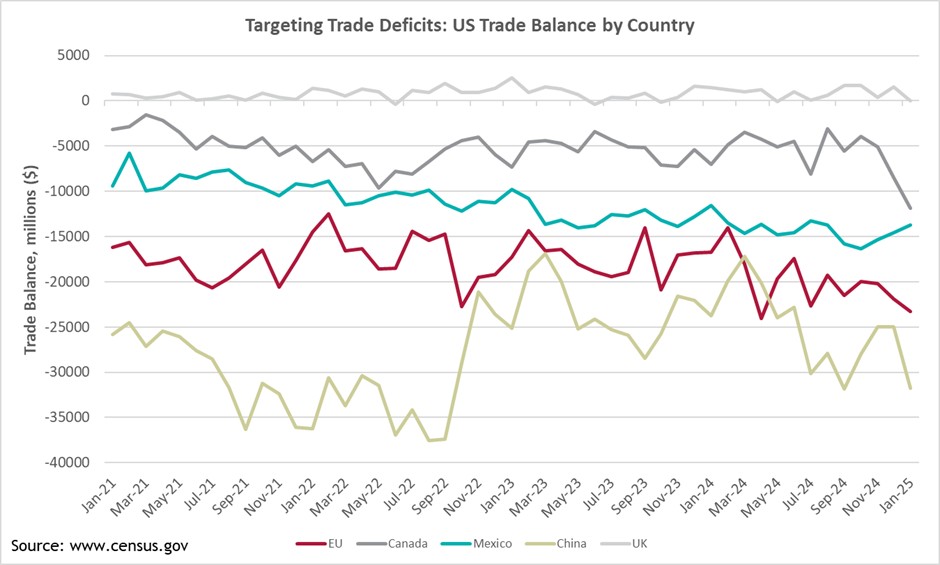

It makes sense that the UK would avoid significant US tariffs, as one of the goals of tariffs is to reduce the trade deficit, which policymakers argue reflects the outsourcing of domestic manufacturing jobs, overreliance on foreign goods, and the transfer of wealth abroad. As shown below, the Anglo-American trade relationship is remarkably balanced and totals nearly £300bn, with the US typically maintaining a slight trade surplus. In the absence of a direct US trade deficit with the UK or similarly serious political grievances, the UK could therefore avoid being directly involved in the US trade wars.

However, it is apparent that the US administration also views sales taxes such as VAT as trade restrictions, despite these taxes being levied on most goods (imported or domestic) in the EU and UK. This raises a risk of tariffs on UK exports despite the relatively balanced trade picture.

So will tariffs be successful in reducing America’s trade deficit? There are several reasons why this may not happen. First, American imports, particularly consumer goods, technology, and industrial inputs are relatively inelastic as they have few domestic substitutes. For example, in the previous US-China trade war that started in 2018 electronics, machinery, and apparel imports from China remained strong despite tariffs because there were limited cost-effective alternatives. Additionally, many of the goods tariffed in that trade war were not reshored and were merely imported from other countries. Secondly, US exports, particularly in agriculture and energy, tend to be more elastic meaning that when tariffs are imposed on US goods (due to retaliation), foreign buyers will likely shift to other suppliers. When these two effects are taken together, the asymmetry in elasticities may even lead to a worse trade deficit, rather than reducing it.

Moreover, the US trade deficit is not solely a function of trade policy but is fundamentally tied to broader macroeconomic factors – specifically, the balance between national savings and investment. Because tariffs do not alter these underlying dynamics, except perhaps to reduce foreign investment in the US, they fail to address the root cause of trade imbalances. Much like in Britain, where deindustrialisation and the expansion of the service sector have contributed to long-term trade deficits, the US trade gap reflects deeper structural shifts in the economy that tariffs alone cannot reverse.

While the effect of tariffs on the US’s trade balance is largely ambiguous, they will likely reshape the US and global economy in many significant ways. Perhaps the primary area of concern among Americans is the effects on US inflation and monetary policy. Inflation is not just a side effect of tariffs but the primary mechanism through which their stated goals are intended to be achieved – namely, higher prices discouraging imports and encouraging consumers to buy domestically. The Yale Budget Lab estimates the inflationary impact to be 1-1.2%. Higher inflation estimates such as these, all else being equal, would suggest that the pace of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve could slow, although the Fed will weigh whether the one-off price increase will feed into domestic inflationary expectations and therefore become more entrenched.

Changes to monetary policy also depend on US economic growth. Here, the immense optimism for the US economy heading into 2025 has shifted significantly. The Atlanta Federal Reserve’s GDPNow model estimated a contraction of -2.4% on March 6th, a significant revision from its earlier forecast of 2.3% growth on February 19th. This dramatic adjustment is primarily driven by a widening trade deficit, declining consumer spending, and reduced business confidence due to trade policy. While other estimates vary significantly from this estimate, increased tariffs stemming from trade deficit concerns are expected to reduce US growth by 0.7-1.1%, according to models by Morgan Stanley. The rationale for this lower growth projection is based on higher production costs for businesses, retaliatory tariffs reducing revenues and investment, and increased uncertainty leading to lower investment, which in turn suppresses productivity growth and economic expansion.

This complicates the forecasting of US monetary policy, as a scenario of lower growth and higher inflation creates a policy dilemma: Should the Fed raise rates to curb inflation at the risk of further depressing growth or lower rates to stimulate growth while running the risk of higher inflation? Markets appear to expect the latter outcome, suggesting that concerns over slowing growth outweigh inflation risks, possibly due to the one-off impact of tariffs. This is reflected in CME implied target rate probabilities, which indicate higher chances of rate cuts through the rest of the year.

The US economy will not be the only one experiencing slower growth. As one of the largest trading partners of the US, the EU faces significant challenges from the expected tariffs. The Kiel Institute estimates that these tariffs could shrink the EU’s already sluggish economy by 0.4%, with the impact concentrated in industries such as automobiles, machinery, and luxury goods.

As an open economy reliant on good imports, the UK will be affected by trade wars whether or not it is directly targeted by tariffs. Export growth is likely to be indirectly affected by slower growth in its main trading partners and inflation could be affected by rising price levels elsewhere. Potentially the UK could also benefit by positioning itself as an alternative supplier for American imports, particularly in sectors where it competes with the EU, such as automobiles and pharmaceuticals, and also a substitute for US goods where it is competitive.

Regardless of the specific details of future US trade policies or the outcomes discussed here, the current US administration is increasing market uncertainty, straining its North American and transatlantic relationships, and undermining the international free trade order it helped establish. Collectively, these actions have contributed to heightened market volatility and underscore the importance of diligent monitoring.

If you would like more information on our economic forecasting, please contact us at treasury@arlingclose.com or 08448 808 200.

Related Insights

Will the US withdraw from Multi-lateral Development Banks? – Credit Market Implications