March is traditionally a bumper month for local authority borrowing, as cash runs out and spending increases during the last quarter. In March 2020, the LA to LA market experienced a severe lack of liquidity due to a perfect storm of events, one of which was the excessive PWLB rate margin implemented by HM Treasury. The liquidity squeeze drove spreads to over 200 basis points for short term loans, a localised credit crunch a la 2007.

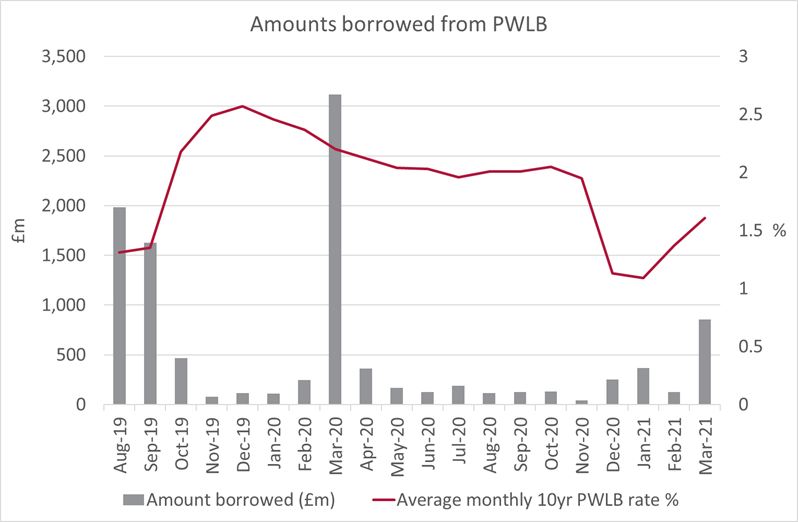

The pandemic and the changes to the PWLB margins prompted a very different March 2021. Cash levels at many local authorities have remained elevated either due to central government funding, whether extra cash, front-loaded grants or the need to act as a distribution agent for local businesses, or more significant pandemic-related budget underspends on capital projects. Despite this, March 2021 PWLB borrowing totalled £850m, the highest single month amount since the £3.2bn borrowed in March 2020, and before that, £1.6bn in September 2019.

The larger amount borrowed in March, despite the apparent surplus of liquidity in the LA to LA market was indicative of two issues: the expectation that elevated cash balances are temporary, and that delayed, and more ambitious capital programmes need funding when rates are at their most affordable. There is no doubt that the sharp rise in longer term borrowing rates in Q1 2021 raised some concerns about budgeting and capital delivery, prompting some authorities to pick up long-term funding where possible to avoid borrowing at potentially higher rates in future. Many authorities have a positive outlook when it comes to capital programmes, seeing opportunities to boost delivery this year to make up for delays last.

But the amount borrowed in March remains small when compared to the dearth of PWLB borrowing in the preceding months; particularly when interest rates were at similar levels to those that prompted around £3.5bn of new borrowing in September and October 2019. As cash balances dwindle over the next six months, the focus will no doubt turn to longer term funding and the various options available; despite the cut in the PWLB margin back to pre-October 2019 levels, the PWLB is certainly not the only game in town.

The government announced the National Infrastructure Bank in the Budget, and while we await further details, there is a chance that this will start lending to local authorities for qualifying projects from mid-2021/22. Arlingclose recently hosted a webcast on this subject with Mark Dennison of Eversheds Sutherland, available here.

Meanwhile, the private sector has found that it is possible to be competitive with the PWLB, particularly when the offering is more flexible. Forward starts and facility arrangements will find favour among borrowers concerned about the possibility of rising rates. Structured finance is also a possibility amid competitive demand from pension funds. Income strips as a form of developer finance may tick the boxes for some authorities, especially where this removes development risk.

In terms of borrowing, 2020/21 will be marked up as a very unusual year, when attention was focused on the more important issues around the pandemic rather than funding the capital programme. However, 2021/22 will hopefully bring with it a level of normality that will allow a renewed focus on meeting those capital spending commitments.

Related Insights:

The National Infrastructure Bank

Support Underpins Local Authority Credit Quality

Scratching Your Head Over Year End?